Tags

Related Posts

Share This

|

|

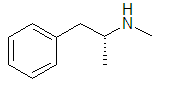

The powerful and neatly packaged video series Meth Inside Out uses a number of techniques to convey its message, from eye-opening graphics to gritty re-enactments using the addicts it portrays to a healthy dose of buzzwords about the disease of addiction. In essence, it approaches its subject with the same thoroughness with which methamphetamine devastates lives. The series of three DVDs has clear value as a patient education tool, as it walks viewers through typical scenarios during an assessment, group therapy, relapse, etc. But having watched the video during a week when a major national pharmacy chain was slapped with hefty fines for not sufficiently safeguarding the commonly sold ingredients used to make meth, I was reminded that these videos also should get into the hands of policymakers. If for nothing else, they manage to show hope amid the often portrayed chaos, and that there remains a reason not to give up on the meth addict. Meth Inside Out (www.methinsideout.com) was produced jointly by Eyes of the World Media Group, which focuses on issues of local and global concern, and the UCLA Integrated Substance Abuse Programs, which stands atop the list of authorities on meth research. The second video of the three, on Brain and Behavior, employs an effective graphic presentation of neuronal activity triggered by drug use; it should stay with the viewer long after watching the series. Narrated by Kristin, a woman seen consistently on screen who has five years of recovery from meth addiction, the series deftly combines first-person accounts with important data about meth (it is the only illegal drug that women use as much as men; it produces a rush three times stronger than cocaines, and lasting four times longer). Significantly, the producers have not shied away from any topic in describing meths damage or its aftereffects; this helps to show clearly how meth destroys normal lives, and then how that normalcy can be regained. One woman in the videos started using in order to lose weight after her pregnancy; a number of gay men got caught up in a culture where use has been seen as helping to reduce shame and inhibitions. Recovery is portrayed not as a straight line but as a process where self-doubt is prevalent and relapse remains likely. One woman describes having been clean for six years and then using one night after fellow members of her PTA group brought out the drug at a meeting. Recovering addicts are warned in a group therapy session about external and internal triggers, and are told that sexual relationships in recovery will feel flat for a period of time. Just as the addicts portrayed in Meth Inside Out started using for different reasons, they also pursued a variety of paths to recovery. For some, the risk of losing a job or a family member got them on the treatment track. For others, a judges threat of long-term imprisonment served as the motivating factor. The series makes a compelling case for having multiple entry points to treatment, as well as for the availability of services tailored to special populations, including persons with co-occurring mental illness.

It comes as no surprise that Meth Inside Out has captured the attention of federal leaders as a research-based tool for patient education and treatment. Beyond these settings, it wouldnt hurt for community leaders to heed the series message of redemption as well.  Gary A. Enos, Editor Addiction Professional 2010 November-December;8(6):6

|

Related Articles

- Editorial: Fast action needed in meth combat (knoxnews.com)